In modern networking, two primary types of cables are used to connect devices: Copper Unshielded Twisted Pair (UTP) and Fiber Optic cables. Both types have their specific uses, advantages, and limitations based on distance, speed, and the type of environment. Let’s dive deeper into the structure, benefits, and differences of these two critical networking components.

Copper UTP Cabling

Copper UTP cables are widely used in Local Area Networks (LANs) due to their cost-effectiveness and compatibility with existing infrastructure. These cables can reliably carry data over distances of up to 100 meters, which is sufficient for most small to medium-sized networks like offices and campus environments.

Key Characteristics of UTP Cables:

- Cost: UTP cables are less expensive compared to fiber optic cables.

- Construction: These cables consist of multiple pairs of copper wires twisted together to minimize electromagnetic interference (EMI). However, they can still be vulnerable to external interference and data leakage.

- Limitations: Maximum cable length is restricted to 100 meters. Beyond this, data degradation and signal loss occur.

A typical RJ-45 connector is used to connect UTP cables to networking devices such as switches, routers, and PCs. However, for larger and more complex networks where distance and speed are critical, copper UTP cabling may not suffice, leading to the need for more advanced cabling solutions.

Fiber Optic Cabling: The Superior Technology

Fiber optic cables are designed for high-performance networking, offering superior speeds and much greater distance capabilities than copper UTP. Instead of carrying electrical signals, fiber optic cables use light pulses transmitted through glass fibers, allowing data to travel much faster and further.

Key Components of Fiber Optic Cables:

- Core: The inner glass fiber through which light travels.

- Cladding: Surrounds the core and reflects light back into it to maintain signal strength.

- Protective Buffer: Adds mechanical protection to the core and cladding.

- Outer Jacket: The external covering that shields the inner layers.

Fiber optic cables consist of two main types: single-mode fiber (SMF) and multimode fiber (MMF).

Single-Mode vs. Multimode Fiber

Single-Mode Fiber (SMF):

- Core: Narrower core diameter (typically 8-10 microns) compared to multimode fiber.

- Light Transmission: Light travels in a single straight path through the core, which minimizes signal loss and allows for longer transmission distances.

- Distance: SMF supports much longer distances, up to 10 kilometers or more depending on the Ethernet standard, making it ideal for long-distance communication such as data centers and metropolitan area networks.

- Cost: More expensive than multimode fiber due to the use of laser-based transmitters.

Multimode Fiber (MMF):

- Core: Wider core diameter (50-62.5 microns), allowing multiple light modes to pass through the fiber.

- Light Transmission: Light bounces at different angles within the core, leading to higher attenuation and shorter transmission distances.

- Distance: Supports shorter distances compared to single-mode fiber, typically around 550 meters for Gigabit Ethernet.

- Cost: Less expensive due to the use of LED-based transmitters, which are cheaper than laser-based transmitters.

Fiber Optic Standards

Fiber optic Ethernet standards determine the maximum distances and data transfer speeds for both multimode and single-mode fibers. Here are some common standards:

- 1000Base-LX: Supports 1 Gbps Ethernet over both single-mode and multimode fiber. Maximum distances are up to 550 meters for multimode fiber and 5 kilometers for single-mode fiber.

- 10GBase-SR: Designed for 10 Gbps Ethernet over multimode fiber, supporting distances up to 400 meters.

- 10GBase-LR: Also supporting 10 Gbps, but over single-mode fiber, it can cover distances up to 10 kilometers.

- 10GBase-ER: Extends the range further, up to 30 kilometers, also operating over single-mode fiber at 10 Gbps.

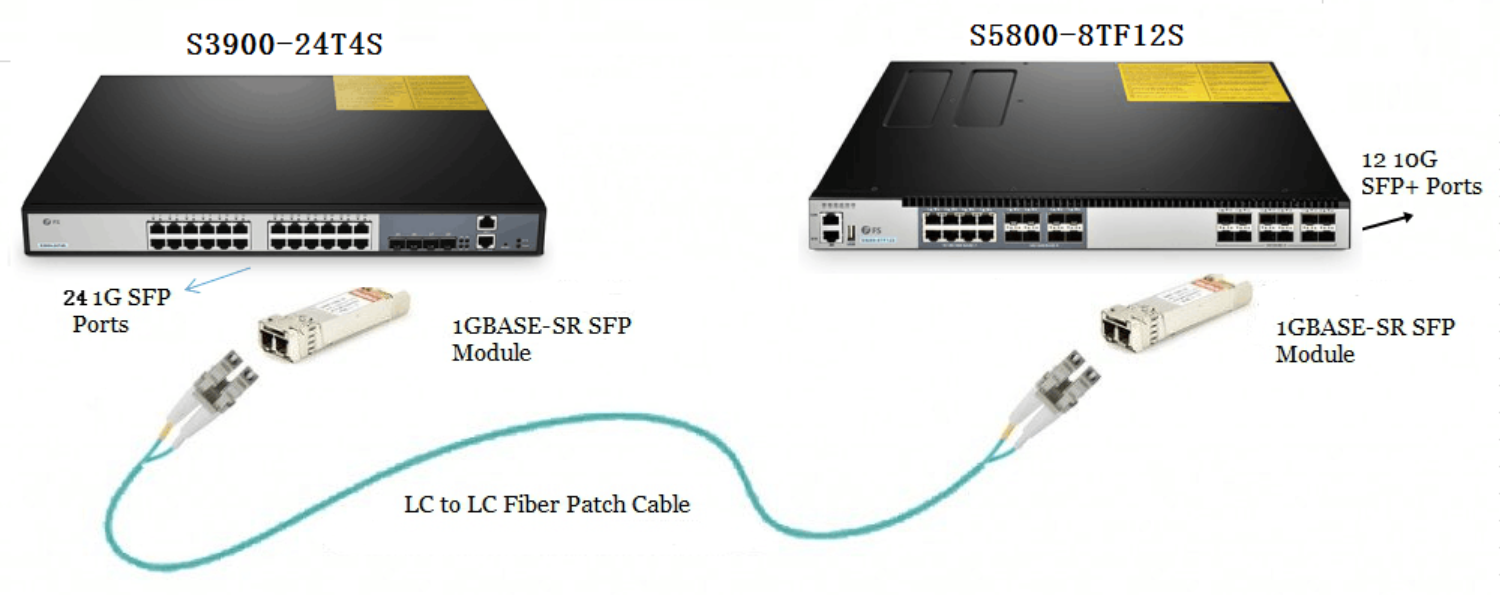

SFP Transceivers and Fiber Connections

Many modern network switches and routers support fiber optic connections through SFP (Small Form-factor Pluggable) transceivers. These transceivers convert the electrical signals from the device into light signals that can travel over fiber. The SFPs are typically inserted into a network device, and a fiber optic cable is connected to the transceiver for long-distance communication.

The fiber optic cables typically use two connectors, one for transmitting and one for receiving data. This ensures that the data flow remains uninterrupted and efficient. Fiber optics, with its superior transmission distance and immunity to EMI, makes it the preferred choice for large-scale networks.

Comparing UTP and Fiber Optic Cables

| Feature | Copper UTP | Fiber Optic |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Cheaper | More expensive |

| Maximum Distance | Up to 100 meters | Up to 30 kilometers (single-mode fiber) |

| Speed | Up to 10 Gbps | Up to 100 Gbps and beyond |

| EMI Vulnerability | Susceptible | Immune |

| Security | Emits signals, potential for leakage | No signal leakage, highly secure |

| Transceivers | RJ-45 ports (cheaper) | SFP transceivers (more expensive) |

The Future of Networking

While copper UTP cables are cost-effective and practical for short-range connections, fiber optics is the clear choice for high-speed, long-distance networking. As technology evolves, the demand for faster, more reliable communication grows, making fiber optics indispensable in data centers, enterprise networks, and internet backbones. For those building or upgrading networks, understanding the advantages and limitations of each cable type is critical for ensuring optimal performance and future-proofing infrastructure.

Conclusion

Fiber optic cabling is the future of networking, offering unparalleled speed, distance, and security. Although copper UTP remains useful in certain scenarios, its limitations are becoming more apparent as network demands increase. Understanding the structure, types, and standards of fiber optic cables, alongside the pros and cons of UTP cabling, equips network engineers and IT professionals to make informed decisions when designing robust and scalable networks.